Manila-Acapulco Route: PH’s Historic Maritime Highway

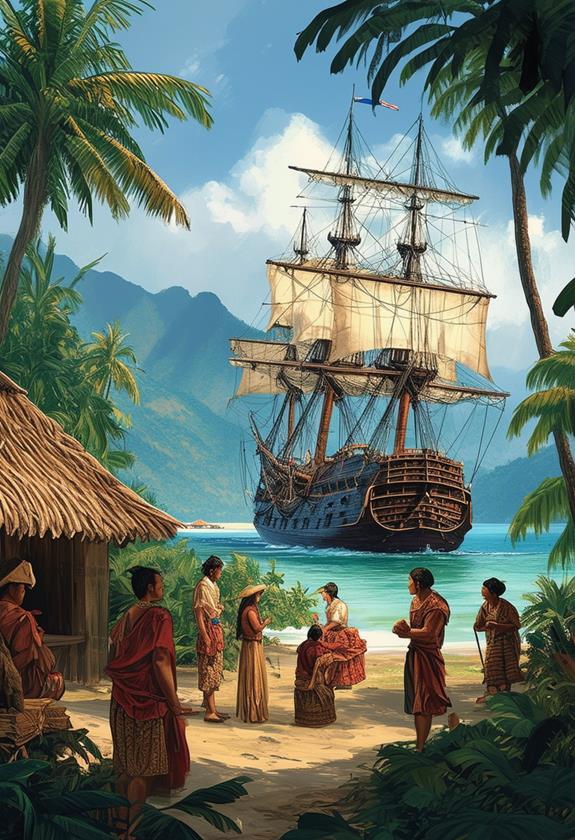

For over 250 years, a legendary maritime highway bridged the continents of Asia and the Americas. This trans-Pacific network, anchored by Spanish galleons, transformed global commerce by linking Manila with Acapulco. Ships carried silver from the Americas to Asia, returning with silk, porcelain, and spices that fueled Europe’s luxury markets.

More than just a trade corridor, this route shaped the Philippines’ identity. Local shipbuilders in Cavite crafted sturdy vessels using native hardwoods and hemp. Meanwhile, the exchange of goods introduced new cultural influences. Mexican spices blended with Asian traditions, creating a legacy still visible today.

The galleon trade’s influence stretched far beyond commerce. It connected distant economies, making Manila a bustling hub of international exchange. By the early 19th century, this network had laid foundations for modern globalization, leaving an indelible mark on world history.

Key Takeaways

- Operated from 1565 to 1815, spanning over 250 years of trans-Pacific trade

- Connected Manila and Acapulco, enabling silver, silk, and spice exchanges between continents

- Philippine shipbuilders used native materials like teak and hemp to construct durable galleons

- Fueled global commerce and positioned Manila as a key international trade hub

- Cultural exchanges between Asia, the Americas, and Europe enriched Filipino heritage

- Paved the way for early globalization through economic and cultural integration

Introduction to the Manila-Acapulco Route

Spanish navigators cracked the Pacific’s code in 1565, unlocking a sea path that reshaped global trade. This breakthrough came through Andrés de Urdaneta, whose discovery of the tornaviaje return route made transoceanic exchanges possible. His navigational genius allowed ships to harness winds and currents for safe westward journeys.

Blueprint of Trans-Pacific Trade

Miguel López Legazpi spearheaded the 1564 expedition that established Spain’s foothold in Asia. His fleet’s arrival in Cebu marked the start of systematic voyages. The first successful round trip in 1565 proved the route’s viability:

| Year | Navigator | Milestone |

|---|---|---|

| 1564 | Legazpi | Launched expedition from Mexico |

| 1565 | Urdaneta | Charting of return route |

| 1573 | San Pablo | First cargo-laden galleon reaches Acapulco |

Architecting a Maritime Empire

Manila galleons became engineering marvels – some stretching 160 feet with triple masts. These ships carried up to 2,000 tons of silver and Asian goods. A typical voyage lasted 4-8 months, with crews battling storms and scurvy.

“Without Urdaneta’s route, Spain’s Pacific dominance would have collapsed like a waterlogged hull.” – Maritime Historian Carlos Madrid

The system created an economic loop: Mexican silver funded Asian luxuries for European markets. This trade web transformed Manila into what contemporaries called “the Venice of the East”. By 1600, over 100 galleons had completed the perilous crossing.

Historical Context and Early Exploration

When Ferdinand Magellan reached the Philippine Islands in 1521, he unknowingly sparked a maritime revolution. His arrival marked Europe’s first direct contact with the archipelago, though his crew completed the journey without him after local warriors ended his expedition in Cebu.

Early Explorations and Discoveries

Spanish ships faced brutal trials along Asia’s uncharted coasts. Crews battled typhoons near the Mariana Islands and dodged pirates in narrow straits. Shipbuilders in Cavite and Cebu soon crafted sturdy galleons using Philippine hardwoods, with some vessels reaching 2,000 tons in capacity.

Magellan’s Expedition and Its Impact

Though Magellan perished in Mactan, his voyage proved Spanish claims in Asia. His logs revealed potential trade routes and resources. Later captains used these records to establish vital ports like Cebu and Manila, creating hubs for repairs and resupply.

Andrés de Urdaneta’s Breakthrough

The aging navigator cracked the Pacific’s return code in 1565. By sailing north to catch the Kuroshio Current, he created a reliable eastward path. This discovery transformed scattered voyages into a regular trade system.

“Urdaneta didn’t just find a route – he built a bridge between worlds,”

notes historian Lilia Ramos-Shahani.

These early efforts laid the groundwork for history’s first global trade network. Shipyards buzzed across the Philippine Islands, while navigators mapped safer coastal paths. What began as risky voyages became a thriving maritime highway.

The Manila Galleon Trade: Construction and Crew

Spanish engineers and Filipino craftsmen teamed up to create floating fortresses that conquered the Pacific. Miguel López Legazpi oversaw early prototypes, blending European designs with local materials. These vessels became symbols of Spain’s naval power and Asia’s shipbuilding expertise.

Shipbuilding Techniques and Materials

Philippine teak and mahogany formed the backbone of these wooden giants. Shipwrights selected trees resistant to rot and worms, cutting planks up to 3 feet wide. Manila hemp ropes held masts taller than coconut palms, while bamboo outriggers stabilized decks.

Builders shaped hulls to harness trade winds, creating curved profiles that sliced through waves. López Legazpi‘s team developed watertight compartments – an innovation copied worldwide. One veteran sailor noted: “These ships groaned like living beasts but never broke.”

Life Aboard the Galleons

Spanish officers commanded mixed crews of 300-400 men. Filipino sailors manned the rigging while Mexican gunners guarded cargo holds. Workers stacked Chinese silk and porcelain in wax-sealed chests, securing $12 million worth of goods by today’s standards.

Below decks, crews battled rats and moldy biscuits. A strict hierarchy ruled: captains dined on chocolate while deckhands fought for sleeping space. Four-month voyages tested endurance, with survival rates often below 50%.

Navigational Challenges and Trade Winds

Navigating the Pacific during the galleon era was a deadly gamble between man and nature. Sailors faced months-long journeys through waters where hidden islands lurked like teeth in a shark’s jaw. Over 90% of shipwrecks occurred near the Philippines’ western islands, where reefs shredded hulls and typhoons swallowed entire fleets.

Overcoming the Pacific’s Perils

The San Bernardino Strait became a notorious killer. Its whirlpools dragged down the Santo Cristo de Burgos in 1693, drowning 400 souls and 1,200 tons of Chinese silks. Captains timed departures to June, racing against monsoon winds that could add extra months to voyages.

Crews battled scurvy while guarding chests of Mexican gold and Asian spices. “One wrong turn meant losing a king’s ransom,” wrote navigator Alonso de Arellano in 1565. Ships like the San Felipe vanished during typhoons, their cargoes lost to coral graves.

By the 18th century, improved charts helped sailors dodge reefs around islands like Lubang. Captains mastered the tornaviaje return path, using trade winds to cut voyage times. These hard-won skills turned deadly crossings into reliable trade highways.

Economic Impact and Cultural Exchange

The flow of silver across the Pacific reshaped economies from Mexico to Manila, creating history’s first global marketplace. Asian silks met American metals in a dance of supply and demand that spanned three continents. This exchange didn’t just move goods—it rewrote the rules of international commerce.

Trade Commodities and Global Markets

Spanish ships carried 55 tons of silver annually to Asia during the galleon trade’s peak. Chinese merchants traded this precious metal for:

| Region | Key Exports | Market Impact |

|---|---|---|

| China | Silk, porcelain | 90% of cargo value |

| Mexico | Silver coins | Funded Asian purchases |

| Philippines | Hemp, hardwoods | Shipbuilding materials |

The trade route created strange economic bedfellows. Mexican miners worked alongside Filipino sailors to sustain this transoceanic pipeline. “Silver became the world’s first true global currency,” notes economic historian Diego del Castillo.

Cultural Influences in the Philippine Islands and Beyond

Food markets tell the story best—Mexican corn now grows beside Chinese bok choy in Philippine fields. The Nuestra Señora figureheads on ships blended Catholic symbols with Asian carving techniques, creating unique religious art.

Language absorbed new words like tsokolate (chocolate) from Mexico. Even children’s games changed, incorporating Spanish counting rhymes with local melodies. These fusions show how the galleon trade became more than economic—it was cultural alchemy.

“Every sack of silver bought a piece of someone else’s world.”

Key Figures and Milestones in the Galleon Era

Visionaries and adventurers charted courses that rewrote maps and forged empires. Their journeys blended ambition with danger, creating a network of oceanic pathways that shaped nations. Three elements defined this era: pioneering navigators, high-stakes voyages, and cargo that ignited global desires.

Exploratory Leaders and Navigators

Ferdinand Magellan’s 1521 arrival in the Philippines opened Asia to European powers, though he never completed the journey. Andrés de Urdaneta’s 1565 return voyage from Cebu to Mexico proved the Pacific could be reliably crossed. These men faced typhoons, scurvy, and mutinies while mapping paths others feared to sail.

Miguel López de Legazpi solidified Spanish control by establishing Manila as a trade hub in 1571. His leadership turned scattered land claims into a coordinated system. Ship captains like Juan de Salcedo later secured vital ports, ensuring safe havens for weary crews.

Historical Voyages and Notable Captures

The San Pablo made history in 1567 by delivering 50 tons of Mexican silver to Asia. Pirates coveted these shipments—English privateer Thomas Cavendish seized the Santa Ana in 1587, capturing silks and porcelain worth millions today.

Key cargo defined the era’s economy:

- Chinese cloth dyed with rare pigments

- Delicate porcelain surviving 8-month voyages

- Spices like cinnamon preserved in wax-sealed jars

Strategic land stops determined success. Ships replenished at Guam before braving the Pacific’s open stretches. Each safe arrival in Acapulco sparked festivals celebrating crews who cheated death for profit.

“These sailors didn’t just move goods—they moved history.”

The Legacy of the Manila-Acapulco Route

Centuries-old trade practices still shape how nations connect across oceans. This maritime network created patterns that modern systems follow, from cargo shipping lanes to cultural diplomacy. Its influence echoes in boardrooms and coastal communities alike.

Influence on Global Trade and Maritime History

The waters once crossed by galleons now carry 90% of global goods. Modern container ships trace paths similar to historic routes, proving the enduring value of these sea lanes. Key innovations from the era still matter:

- Standardized trade agreements between nations

- Risk-sharing models for international shipments

- Multicultural crew management practices

Soldiers and officers developed early security protocols against pirates—methods adapted by today’s naval forces. The way goods moved between continents set the stage for free trade zones and economic blocs like ASEAN.

Modern Recognition and Heritage Initiatives

Three nations now collaborate to preserve this shared history. The Philippines, Mexico, and Spain nominated the trade network for UNESCO World Heritage status in 2023. Key projects include:

- Digital archives of ship logs at Manila’s Naval Museum

- Restored shipyards in Cavite showing traditional construction ways

- Annual cultural festivals featuring Mexican folk dances and Filipino cuisine

Local people lead walking tours through Acapulco’s historic docks, sharing stories of ancestors who loaded silver onto creaking galleons. As one historian notes:

“This route wasn’t just about goods—it taught humanity how to work across borders.”

Conclusion

The daring voyages across the Pacific forged connections that still resonate today. This maritime network transformed isolated regions into linked civilizations, blending traditions through silks, spices, and shared human resilience.

Brave men navigated deadly storms during months-long crossings, while passengers carried cultural knowledge between continents. Their journeys required perfect timing—launching with seasonal winds and racing against hunger and disease. Many never completed the passage, their stories lost to the sea.

These crossings birthed the first global economy. Mexican silver funded Asian craftsmanship, creating trade patterns still visible in modern shipping lanes. The Manila-Acapulco Route proved that distant lands could thrive through cooperation, despite vast oceans separating them.

Today, museums and festivals honor this legacy. Ship replicas sail historic passages, reminding us how courage and curiosity shaped our world. For historians and sailors alike, these voyages remain timeless lessons in perseverance and cultural exchange.