How Mexican Silver Changed Filipino Trade Forever

For over two centuries, a powerful exchange reshaped economies across continents. Ships laden with precious metals sailed vast oceans, connecting distant cultures through commerce. This story begins with the Manila Galleon, a maritime marvel that linked Asia and the Americas starting in 1565.

At the heart of this system lay a glittering resource: silver mined in New Spain. Asian markets craved this metal, trading luxurious silks, porcelain, and spices in return. The Philippines became a bustling crossroads where East met West, fueled by endless shipments of this valuable commodity.

The galleons didn’t just carry cargo. They transported ideas, technologies, and traditions between continents. Port cities like Manila thrived as hubs of cultural fusion, while colonial powers competed for dominance. This network laid foundations for modern globalization.

Beyond wealth, these routes transformed societies. Local economies adapted to meet global demands, creating new industries and trade partnerships. Even after the galleons stopped sailing in 1815, their legacy endured in financial systems and international relations.

Key Takeaways

- The Manila Galleon operated for 250 years, creating the first intercontinental trade route.

- Silver from New Spain mines became the primary currency for Asian luxury goods.

- Manila emerged as a critical hub connecting three continents through maritime trade.

- Cultural exchanges occurred alongside commercial transactions, influencing art and traditions.

- This system established patterns still visible in today’s global economy.

Historical Context of the Galleon Trade

The 16th century saw European powers racing to unlock Asia’s riches through uncharted waters. Ferdinand Magellan’s 1521 arrival in the Philippines marked Europe’s first sustained contact with the archipelago. His expedition opened doors for Spain, though completing the Pacific crossing remained elusive for decades.

European Expansion and Asian Connections

Andrés de Urdaneta cracked the Pacific puzzle in 1565. His tornaviaje return route transformed Manila into a global crossroads. Sailors could now harness wind patterns to connect Acapulco with Asian ports reliably.

This breakthrough answered Europe’s craving for spices and silks. Asian markets demanded silver, creating a perfect exchange system. The Manila-Acapulco route became history’s longest continuous maritime highway.

The Emergence of Global Trade Routes

Spain’s galleons didn’t just carry cargo—they wove continents together. Ships transported Chinese porcelain to Mexico City markets within months. Mexican silver reached Canton merchants faster than European gold.

Four key developments shaped this network:

- Magellan proving Asia’s western accessibility

- Urdaneta’s navigation breakthrough

- China’s insatiable silver demand

- Spain’s colonial infrastructure in the Americas

These factors birthed a trade web spanning three oceans. Ports like Manila buzzed with multilingual traders, laying groundwork for today’s interconnected markets.

The Manila Galleon: Symbol of a New World Trade System

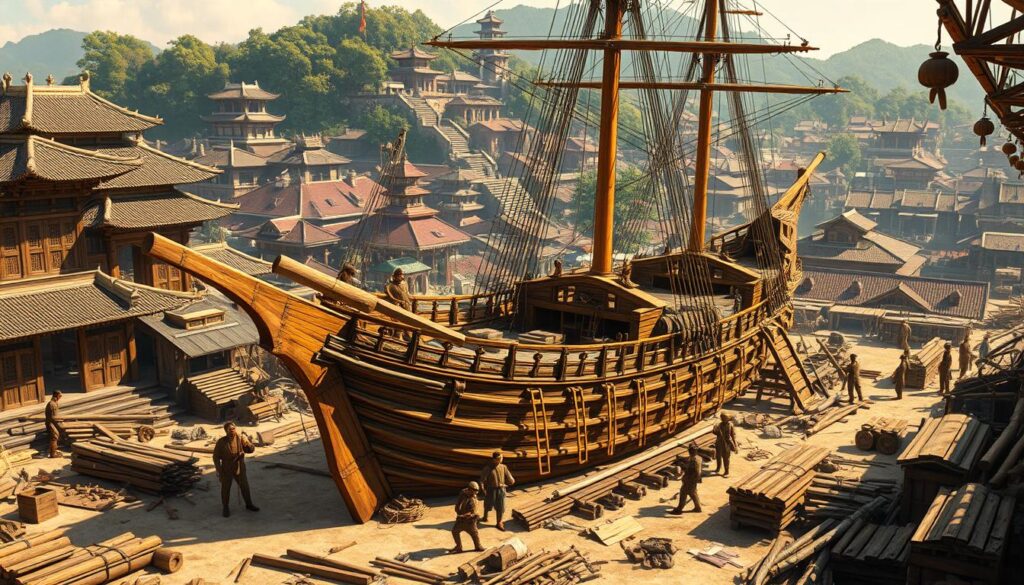

Massive wooden giants ruled the Pacific waves for centuries. These floating fortresses carried more than cargo—they represented a revolution in maritime engineering. Built in Philippine shipyards, the Manila galleons combined European designs with Asian craftsmanship to create the era’s most durable vessels.

Ship Construction and Technological Innovations

Philippine hardwoods like molave and banaba became the backbone of transoceanic travel. Shipwrights selected timber that could endure 6-month voyages through typhoons and saltwater corrosion. The Sacra Familia, launched in 1718, showcased curved hulls that sliced through waves while carrying 1,500 tons of cargo.

Three key innovations defined these galleons:

- Triple-layered plank systems for hull reinforcement

- Hybrid sail configurations balancing speed and stability

- Watertight compartments inspired by Chinese junk designs

Manila Shipyard Expertise

Cavite and Bagatao shipyards buzzed with activity year-round. Local artisans perfected ships using techniques passed through generations. Spanish records noted:

“Filipino carpenters assemble vessels faster and sturdier than any European dockyard”

| Feature | Spanish Method | Filipino Technique |

|---|---|---|

| Deck Material | European oak | Apitong hardwood |

| Nail Usage | Iron spikes | Wooden dowels |

| Hull Design | Flat-bottomed | Curved waterlines |

| Construction Time | 2-3 years | 8-12 months |

This blending of traditions created a system that outpaced European rivals. Philippine-built galleons dominated Pacific trade routes until steam power changed maritime rules two centuries later.

The Role of Mexican Silver in Trade Economics

In the 16th century, a metallic tide flowed from New Spain, fueling empires and markets. This precious metal became the lifeblood of intercontinental commerce, shaping financial systems from Manila to Madrid.

Silver as the Currency of Global Commerce

Mines in Zacatecas and Potosí produced staggering quantities – over 25,000 tons by 1600. Each Manila galleon carried up to 3 million silver pesos, equivalent to $150 million today. Asian merchants exchanged silks and spices for these coins, creating history’s first truly global currency.

China’s Single Whip Reform (1581) mandated tax payments in silver, boosting demand. Spanish records note:

“The wealth of nations now resides in these stamped discs from New Spain“

Economic Impact on the Spanish Empire

Flooding European markets with silver caused 400% inflation within a century. Yet this metal bankrolled Spain’s global dominance. While gold symbolized prestige, silver’s sheer volume – ten times Europe’s output – powered practical transactions.

Three economic shifts emerged:

- Manila became Asia’s silver exchange hub

- Colonial mines funded Spain’s military campaigns

- Intercontinental price systems developed through bullion flows

The trade network birthed in New Spain redefined value itself, proving that currency could bridge civilizations as effectively as ships crossed oceans.

How Mexican Silver Changed Filipino Trade Forever

A metallic flood from the Americas rerouted centuries-old trading networks. When Andrés de Urdaneta unlocked the Pacific’s return route in 1565, maritime traffic patterns shifted dramatically. This navigation breakthrough created a 250-year corridor (1565-1815) that bypassed traditional Asian land routes.

Shifts in Trading Patterns and Maritime Routes

Merchant vessels began favoring direct crossings between Acapulco and Manila. The trade route reduced travel time from 18 months to 6 through optimized wind patterns. Ships increased from annual departures to three voyages yearly during peak periods.

Cargo manifests transformed as silver stocks grew. Records show galleons carried 50% more precious metal by weight after 1600. Crews became multinational mixes – Spanish captains oversaw Filipino navigators and Mexican porters.

Three key adjustments reshaped commerce:

- Chinese junks redirected to Manila instead of Southeast Asian ports

- Philippine coastal villages became supply stations for passing galleons

- Spanish authorities imposed strict cargo limits after 1700 to prevent overloading

This route remained active until 1815, adapting to changing political climates. As one Mexican trader noted:

“Our ships became floating markets where silks met silver before either touched European soil”

The system’s longevity proved how trade routes could reshape regional economies through sustained maritime connections.

Impact on the Philippine Local Economy and Culture

Cultural tides reshaped Philippine shores as ships unloaded more than cargo. Daily life transformed through blended traditions and new economic patterns. Markets buzzed with foreign fabrics, while fields grew unfamiliar crops from distant lands.

Cultural Exchanges and Spanish Influences

Spanish friars introduced European farming tools, revolutionizing rice cultivation. Local weavers adopted loom techniques to create hybrid fabrics like piña-seda – pineapple silk blended with Chinese threads. This textile later inspired the iconic Manila shawl worn in Spanish flamenco dances.

Language absorbed over 4,000 Spanish terms. Words like kutsara (spoon) and bintana (window) entered daily speech. Religious festivals merged indigenous rhythms with Catholic imagery, creating vibrant celebrations still practiced today.

Adoption of New Customs and Traditions

Urban centers swelled as ports attracted global settlers. By the 18th century, Manila housed Chinese merchants, Mexican traders, and Malay artisans. This mix birthed unique dishes – adobo combined Spanish vinegar stews with local coconut milk.

| Aspect | Pre-Colonial | Colonial Era |

|---|---|---|

| Agriculture | Root crops | Maize & tobacco |

| Textiles | Abaca fiber | Silk blends |

| Language | Malay roots | Spanish loanwords |

| Cuisine | Boiled meats | Marinated dishes |

| Urbanization | Coastal villages | Walled cities |

The country’s social fabric changed as people adapted foreign ideas to local needs. Traditional barangay leadership systems merged with Spanish town councils. This cultural alchemy shaped national identity long after the last galleon sailed.

Navigation and Sea Routes of the Manila Galleon

Sailing east across the Pacific presented an impossible puzzle for 16th-century mariners. This changed when Andrés de Urdaneta unlocked nature’s hidden pathways. His discovery transformed oceanic travel, creating reliable connections between continents.

Urdaneta’s Tornaviaje Discovery

The Augustinian friar made history in 1565 by sailing from Manila to Acapulco in 129 days. Urdaneta exploited the Kuroshio Current, a powerful north-flowing stream that pushed ships toward North America. This “return voyage” system relied on precise celestial navigation and wind pattern analysis.

Previous attempts failed because captains sailed too far south. Urdaneta’s route arced northward to 38° latitude before catching east-blowing westerlies. A Spanish sailor’s diary noted:

“We rode Heaven’s breath across empty waters, trusting the stars more than our maps”

Currents, Challenges, and Seasonal Voyages

Timing proved critical for successful crossings. Ships departed Manila in June to catch southwest monsoons, then raced against autumn typhoons. The Pacific Ocean tested crews with its vastness – 15,000 km of open water with no land sightings for months.

Three factors dictated voyage duration:

- Storm avoidance added weeks to routes

- Food spoilage limited travel windows

- Current shifts could trap ships in doldrums

Most crossings took 6-8 months, though records show extremes from 4 to 11 months. Navigators used estima dead reckoning, often missing Acapulco by hundreds of miles. This delicate dance with nature sustained the trade route for generations.

Architectural and Design Mastery of the Galleons

Shipwrights transformed Philippine forests into floating fortresses through precision engineering. Their creations carried empires’ wealth across oceans while battling storms and pirates. Each vessel represented a marriage of European naval architecture and Asian material science.

Vessel Construction Techniques and Materials

Builders selected molave and narra hardwoods for their saltwater resistance. These dense timbers formed triple-layered hulls that could survive 15,000-mile voyages. A typical galleon displaced 1,200-2,000 tons, requiring meticulous weight distribution for stability.

Cargo holds were engineered like puzzle boxes. Delicate porcelain from Jingdezhen sat in straw-lined compartments below deck. Rolls of Chinese silk occupied waterproof chests near the centerline. This careful arrangement prevented shifting during rough seas.

| Material | Source | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Apitong wood | Luzon forests | Deck planking |

| Abaca fiber | Visayas region | Rope production |

| Bamboo | Local plantations | Scaffolding |

Shipyards near Manila Bay perfected curved hull designs to slice through waves. Artisans used wooden dowels instead of iron nails to prevent rust corrosion. As one Spanish observer noted:

“Their ships swallow the ocean’s fury like leviathans laughing at tempests”

This engineering legacy lives on in modern cargo ships. The same principles of balanced weight distribution and durable materials still guide vessel construction today.

Transformation of Global Markets in the 16th-18th Century

Three continents became economically entwined through unprecedented exchanges of rare commodities. By the 16th century, Manila’s docks overflowed with goods bound for distant markets. This era saw regional trade networks merge into a planetary web of commerce.

Rise of Luxury Goods and Trade Networks

Asian silks met American cochineal dyes in Manila’s warehouses, creating vibrant fabrics for European nobles. Records show a 700% increase in porcelain shipments between 1580-1620. Spices like cloves traveled from Moluccas to Mexico City kitchens within a year.

Four factors drove market integration:

- China’s demand for silver reshaped currency systems

- Spanish colonies produced high-value dyes and metals

- European elites craved exotic Asian luxuries

- Improved maritime routes reduced transport costs

| Century | Key Goods | Annual Value (Silver Pesos) |

|---|---|---|

| 16th | Spices, Silk | 2 million |

| 17th | Porcelain, Cochineal | 4.5 million |

| 18th | Tea, Saltpeter | 8 million |

Saltpeter shipments from Manila to Europe supported gunpowder production, linking warfare to commerce. A Spanish merchant noted:

“Our ships carried the ingredients for both banquets and battles”

This system laid foundations for modern supply chains. Prices in Canton began influencing markets in Cadiz, creating history’s first synchronized global economy.

The Long Journey: From Asia to the Americas

Crossing the Pacific demanded perfect synchronization with nature’s rhythms. Sailors timed departures to the hour, knowing a week’s delay could add months to their voyage. This precision turned Manila’s port into a hive of activity each summer.

Voyage Timelines and Maritime Navigation

Ships set sail in June to catch southwest monsoons pushing them northeast. By August, they entered the Kuroshio Current – a 4-knot “river in the ocean” flowing toward North America. Most reached Acapulco by December, though storms often extended trips into the new year.

| Phase | Duration | Key Activity |

|---|---|---|

| Departure Prep | April-May | Loading silk, spices |

| Monsoon Ride | June-July | Catching southwest winds |

| Current Navigation | August-October | Riding Kuroshio stream |

| Final Approach | November-January | Avoiding Baja storms |

Captains faced impossible choices when weather shifted. Diaries reveal tense debates:

“Do we risk sinking by storm or starvation by delay?”

Three factors made schedules unpredictable:

- Typhoons rerouting ships by 500+ miles

- Food supplies lasting only 6 months

- No celestial navigation during cloudy weeks

Despite these challenges, 80% of voyages completed within 7 months annually for 250 years. This consistency shaped global trade calendars, proving that even nature’s chaos could be harnessed through careful planning.

Economic and Social Networks in Spanish Colonies

Port cities like Manila and Acapulco emerged as vital links in a global exchange system. These urban centers thrived as meeting points for diverse cultures and commodities. By the 17th century, their docks buzzed with merchants haggling over goods from three continents.

Urban Centers, Marketplaces, and Trade Hubs

The Spanish colonial economy relied on a well-organized network of ports. Manila received Asian luxuries like Chinese porcelain, while Acapulco supplied silver from New Spain. Records show over 4 million pesos worth of goods passed through these hubs annually during peak years.

Marketplaces became laboratories of cultural fusion. Manila’s Parián district hosted Chinese silk traders, Japanese sword merchants, and Mexican cocoa suppliers. A Spanish official noted:

“The market’s cacophony blended Malay, Hokkien, and Castilian into a new mercantile language”

Local products gained international reach through this system. Philippine abaca fibers strengthened ship ropes, while American sweet potatoes entered Asian diets. The table below shows key exchanges:

| Region | Exported Items | Imported Goods |

|---|---|---|

| Manila | Silk, spices | Silver, maize |

| Acapulco | Silver, dyes | Porcelain, tea |

Arrivals of Manila galleons triggered economic booms. Port cities expanded their warehouses and hired extra laborers. This activity created social networks connecting sailors, officials, and craftsmen across oceans.

Artifacts and Cultural Legacy in Modern Trade

Centuries-old trade artifacts still shape global commerce today. Museums display Chinese porcelain from galleon wrecks, while Manila shawls blend Asian and European designs. These relics remind us how early exchanges built bridges between distant cultures.

Timeless Techniques in Global Commerce

Modern cargo ships use methods perfected during the galleon era. Sturdy wooden crates from the 1600s inspired today’s container systems. A Spanish merchant’s diary reveals:

“We stacked silk rolls like playing cards – a practice still seen in Manila’s ports”

Coastal cities retain their strategic importance. Historic ports like Cebu now handle electronics instead of spices. Singapore’s shipping lanes follow paths first charted by galleon navigators.

| Aspect | Historical Practice | Modern Equivalent |

|---|---|---|

| Spice Transport | Clay jars in ship holds | Climate-controlled containers |

| Navigation | Star charts and hourglasses | GPS and automated systems |

| Trade Hubs | Manila’s Parián market | Singapore port complex |

Cloves and nutmeg remain valuable exports from Southeast Asia. These spices now flavor global cuisine and pharmaceuticals. The exchange of goods continues, though cargo planes have replaced wooden ships.

Silver mined in the Americas still impacts economies. Modern bullion markets trace their roots to Acapulco-Manila transactions. Coastal communities preserve boat-building traditions while adopting new technologies.

Unraveling the Complex Trade Systems: Silver, Goods, and Galleons

Interlocking networks of commerce stretched across oceans, binding distant economies into a single operational machine. At its core lay three elements: gleaming silver bars, coveted luxury items, and purpose-built ships that defied maritime limits. This triad created history’s first truly global marketplace.

Integration of Markets Across Continents

Mexico City emerged as the Western Hemisphere’s command center. Officials there coordinated land caravans carrying silver from mines to ports, while managing incoming Asian goods. Records show 60% of all trans-Pacific cargo passed through its warehouses by 1650.

The system relied on synchronized transport:

- Mule trains moved bullion from Zacatecas to Acapulco

- Filipino-built galleons crossed the Pacific laden with silk

- Chinese junks supplied porcelain through Manila’s ports

Enslaved laborers formed the workforce backbone. Over 40% of mine workers and 30% of dock crews were forced laborers. A Spanish ledger from 1598 notes:

“Without native and African hands, our silver never reaches the ships”

Lasting Economic Implications and Global Impact

Modern supply chains mirror these colonial networks. Just as galleon trade routes connected three continents, today’s shipping lanes link manufacturing hubs to consumer markets. Key parallels include:

| 17th Century | 21st Century |

|---|---|

| Manila-Acapulco route | Trans-Pacific shipping corridors |

| Silver standardization | US dollar as reserve currency |

| Mixed-crew vessels | Multinational logistics teams |

The trade system’s collapse in 1815 left enduring lessons. Overreliance on single commodities risks economic instability, while exploitative labor practices sow long-term social fractures. Yet its greatest legacy remains proving that interconnected markets can uplift – or destabilize – nations worldwide.

Conclusion

Centuries of maritime commerce forged connections that still shape our world today. The Manila Galleon network redefined commerce by merging three continents into a single economic exchange system. Asian silks met American metals through Philippine ports, creating patterns that echo in modern supply chains.

This history reveals how resource flows transformed societies. Precious metals from distant mines became the lifeblood of intercontinental deals. Coastal villages evolved into thriving hubs, while shipbuilding techniques crossed cultural boundaries.

The exchange of goods and ideas left permanent marks. Blended textiles, adapted languages, and fusion cuisines emerged from this era. Port cities like Manila remain vital to global networks, proving innovation often springs from cultural collisions.

As we navigate today’s interconnected world, these lessons endure. Modern logistics and financial systems owe much to those early voyages. Their legacy reminds us that commerce thrives when cultures collaborate – a truth as relevant now as in the age of wooden ships.