Cavite Mutiny of 1872: Causes, Effects, and the Gomburza Legacy

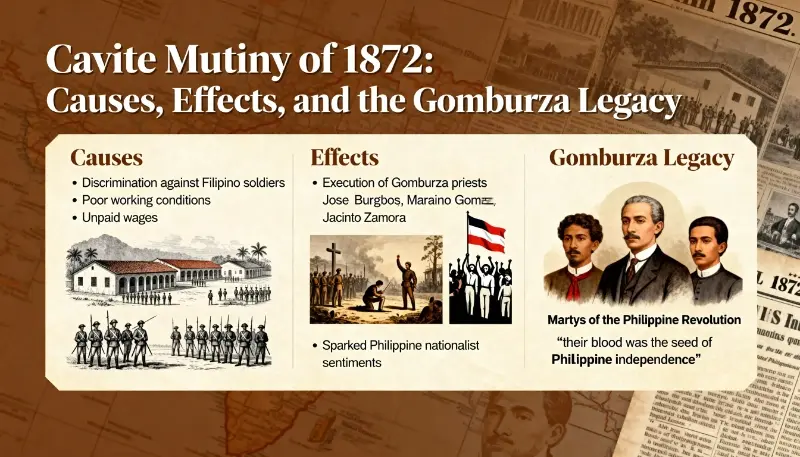

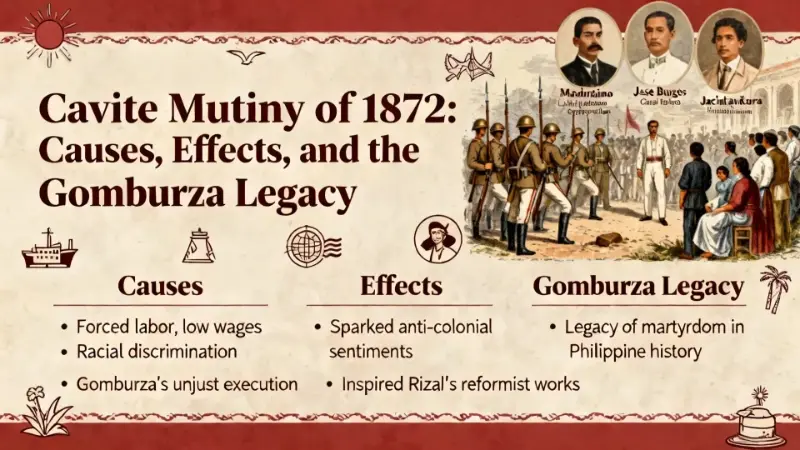

The Cavite Mutiny of 1872 stands as a watershed moment in Philippine colonial history, marking the beginning of organized Filipino resistance against Spanish rule. This uprising at the Cavite Arsenal, though swiftly suppressed, triggered events that would fundamentally alter the trajectory of Filipino nationalism and ultimately contribute to the Philippine Revolution of 1896.

What Is the Cavite Mutiny of 1872?

Definition and Historical Context

The Cavite Mutiny was an armed uprising that erupted on January 20, 1872, at the Cavite Arsenal, also known as Fort San Felipe, in Cavite, Philippines. Approximately 200 Filipino soldiers and arsenal workers seized control of the military installation in response to the Spanish colonial government’s abolition of their long-held privileges.

The event occurred during a period of heightened tension between Filipino workers and Spanish authorities, when the colonial administration under Governor-General Rafael Izquierdo implemented increasingly repressive policies.

Spanish colonial rule in the Philippines, which began in 1565, was characterized by exploitation of Filipino labor, racial discrimination, and the Catholic Church’s dominance over social and political life.

By the 1870s, a growing educated Filipino class, the ilustrados began questioning Spanish authority, while Filipino secular clergy challenged the Spanish friars’ monopoly on ecclesiastical positions. These undercurrents of discontent created fertile ground for resistance.

Key Figures Involved in the Uprising

The mutineers consisted primarily of Filipino soldiers from the Spanish colonial army garrison and native workers employed at the Cavite Arsenal. These men, many of whom had military training, represented the lower strata of colonial society subjected to discriminatory policies.

Governor-General Rafael Izquierdo, appointed in 1871, played a central role in precipitating the mutiny through his authoritarian governance style. His administration reversed liberal policies implemented by his predecessor and imposed stricter control over Filipino populations.

The three Filipino secular priests Mariano Gómez, José Burgos, and Jacinto Zamora, collectively known as Gomburza, became the most prominent figures associated with the mutiny despite their indirect involvement.

Father Mariano Gómez, at 85 years old, was the parish priest of Bacoor, Cavite. Father José Burgos, 35, was an outspoken advocate for Filipino clergy rights and a prolific writer on ecclesiastical reform. Father Jacinto Zamora, 37, served as a parish priest in Manila. Spanish authorities implicated these priests in the uprising, claiming they masterminded a broader conspiracy to overthrow colonial rule.

Causes of the Cavite Mutiny of 1872

Colonial Injustices and Labor Grievances

The immediate catalyst for the mutiny was Governor-General Izquierdo’s decision to abolish the exemptions from tribute payment (falla) and forced labor (polo y servicios) that Filipino workers at the Cavite Arsenal had enjoyed for generations. These privileges represented significant economic relief for workers and their families, and their sudden removal created financial hardship and resentment.

Under Spanish colonial rule, Filipino workers received lower wages than their Spanish counterparts for identical work. They endured harsh working conditions, racial discrimination, and arbitrary punishment. The arsenal workers viewed the abolition of their privileges not merely as an economic setback but as another manifestation of Spanish disregard for Filipino welfare and dignity.

Political Tensions Under Governor Rafael Izquierdo

Rafael Izquierdo assumed the governorship in April 1871, replacing the more liberal Carlos María de la Torre. While de la Torre had relaxed censorship, permitted public assembly, and adopted a conciliatory approach toward Filipinos, Izquierdo reversed these reforms and instituted repressive measures.

Izquierdo increased surveillance of Filipino intellectuals and suspected reformists. He reinstated strict censorship of publications and correspondence. His administration viewed any expression of Filipino identity or criticism of Spanish policies as potential sedition. This climate of suspicion and repression alienated even moderate Filipinos who sought reform within the colonial system rather than revolution.

The governor-general’s authoritarian approach extended beyond political matters. He enforced Spanish cultural dominance, suppressed Filipino cultural expressions, and strengthened the position of Spanish friars against Filipino secular clergy. His policies effectively reversed the tentative liberalization that had begun under his predecessor.

Influence of the Spanish Friars and the Secularization Movement

The conflict between Spanish friars members of religious orders like the Augustinians, Dominicans, Franciscans, and Recollects and Filipino secular clergy formed a crucial backdrop to the mutiny.

Spanish friars controlled parishes throughout the archipelago, wielding enormous political and economic power beyond their religious functions. They resisted the secularization movement, which advocated transferring parish administration from the religious orders to diocesan priests, many of whom were Filipino.

Father José Burgos led the secularization movement, arguing that Filipino priests deserved equal treatment and parish assignments. In numerous writings, he documented discrimination against Filipino clergy and challenged the friars’ justifications for maintaining control. The movement represented not only ecclesiastical reform but also Filipino aspirations for equality and recognition of their capabilities.

Spanish friars perceived the secularization movement as a threat to their power and, by extension, to Spanish colonial control. They characterized Filipino priests as racially inferior and religiously unreliable. This conflict intersected with broader colonial tensions, as the friars possessed significant influence over Spanish authorities and actively opposed any reforms that might empower Filipinos.

The Cavite Mutiny stemmed from three primary causes:

- Economic grievances: The abolition of tax and labor exemptions for Filipino arsenal workers created immediate financial hardship and signaled Spanish disregard for established agreements

- Political repression: Governor-General Izquierdo’s authoritarian policies, increased surveillance, and reversal of liberal reforms created a climate of fear and resentment among Filipinos

- Religious discrimination: The ongoing conflict between Spanish friars and Filipino secular clergy, particularly regarding parish control and ecclesiastical equality, exemplified broader colonial injustices and fueled nationalist sentiments

What Happened During the Fort San Felipe Uprising?

The Night of January 20, 1872

On the evening of January 20, 1872, approximately 200 Filipino soldiers and arsenal workers at Fort San Felipe launched their uprising. Sergeant Lamadrid, a Filipino soldier, led the initial assault. The mutineers seized the arsenal, killed the Spanish commanding officer, and took control of the fort’s weapons and ammunition.

The insurgents expected reinforcements from Manila and support from other military garrisons throughout Luzon. They believed their action would trigger a wider uprising against Spanish rule. However, these anticipated reinforcements never materialized. The mutiny remained isolated to the Cavite Arsenal, with no significant support from other Filipino soldiers or civilians in nearby areas.

The mutineers controlled Fort San Felipe for less than 24 hours. Their lack of coordination with potential allies and the absence of a comprehensive plan for sustaining the rebellion doomed the uprising from its inception.

The Spanish Military Response

Spanish authorities responded swiftly and decisively to the uprising. Governor-General Izquierdo dispatched Spanish troops and loyalist Filipino soldiers to Cavite. The colonial forces, superior in numbers and organization, surrounded Fort San Felipe and launched a counterattack.

By the morning of January 21, Spanish forces had recaptured the arsenal. The mutineers, realizing the hopelessness of their situation without external support, either surrendered or attempted to flee. Spanish troops killed many insurgents during the assault and captured others who attempted escape.

The aftermath brought brutal repression. Spanish authorities arrested dozens of suspects throughout Cavite and Manila. Military tribunals, lacking due process protections, tried the captured mutineers and alleged conspirators. The trials concluded rapidly, with many defendants receiving death sentences.

Spanish forces executed the mutiny’s leaders by firing squad. Dozens of other participants faced imprisonment or deportation to distant Spanish penal colonies in the Marianas Islands and North Africa.

Two Faces of the 1872 Cavite Mutiny: Competing Narratives

The Spanish Colonial Government’s Account

Governor-General Izquierdo and Spanish authorities characterized the Cavite Mutiny as part of an extensive conspiracy to overthrow Spanish colonial rule and establish a Filipino republic. According to this official narrative, Filipino intellectuals, particularly the secular clergy led by Father José Burgos, had orchestrated the uprising as the first stage of a planned revolution.

The Spanish account claimed that the conspirators had established secret societies throughout Manila and surrounding provinces, recruiting Filipino soldiers and civilians to their revolutionary cause. Spanish investigators alleged that the mutineers expected widespread support from other garrisons and the civilian population, which would transform the local uprising into a national revolution.

Izquierdo used this narrative to justify sweeping repression of Filipino reformists, intellectuals, and clergy. By portraying the mutiny as a sophisticated conspiracy rather than a localized labor dispute, Spanish authorities legitimized harsh measures against anyone advocating Filipino rights or reforms. This interpretation served Spanish interests by discrediting the secularization movement and silencing voices calling for colonial reforms.

Spanish friars supported and amplified this conspiracy theory, as it justified their warnings about the dangers of empowering Filipino clergy and intellectuals. The narrative reinforced their position that Filipinos required continued Spanish oversight and that any concessions to Filipino demands threatened colonial stability.

The Filipino Nationalist Perspective

Filipino historians and contemporary observers presented a contrasting interpretation of the mutiny. According to this account, the uprising represented a spontaneous reaction to the abolition of the arsenal workers’ privileges rather than a premeditated revolution. The mutineers acted impulsively, driven by immediate grievances without coordination with alleged co-conspirators in Manila.

This perspective maintains that Spanish authorities deliberately exaggerated the mutiny’s scope and organization to justify eliminating reformist voices. Governor-General Izquierdo and the Spanish friars exploited the incident to settle scores with Filipino secular clergy and intellectuals who challenged their authority through legal means rather than armed rebellion.

Dr. Trinidad Hermenegildo Pardo de Tavera, a Filipino historian and physician who studied the mutiny, concluded that no evidence supported the conspiracy theory. He argued that Spanish authorities tortured prisoners to extract false confessions implicating prominent Filipino reformists. The trials violated basic standards of justice, relying on coerced testimony and circumstantial evidence to convict defendants.

This interpretation emphasizes the political opportunism behind the Spanish response. By transforming a limited uprising into an alleged national conspiracy, Spanish authorities created justification for suppressing the entire reform movement, consolidating friar power, and demonstrating to Filipinos the consequences of challenging colonial authority.

Gomburza: The Martyrdom That Ignited Filipino Nationalism

Who Were Gómez, Burgos, and Zamora?

Father Mariano Gómez, born in 1799 in Santa Cruz, Manila, served as parish priest of Bacoor, Cavite. At 85 years old at the time of his arrest, he had spent decades serving Filipino parishioners. Though not politically active in his later years, his position as a respected Filipino priest made him a target for Spanish authorities seeking to implicate the secular clergy.

Father José Burgos, born in 1837 in Vigan, Ilocos Sur, emerged as the most prominent advocate for Filipino clergy rights. Educated in Manila and an accomplished scholar, he wrote extensively on the injustices Filipino priests faced under Spanish friar dominance. His publications documented specific cases of discrimination and argued for the intellectual and moral equality of Filipino clergy.

Burgos advocated reform through legal channels and religious arguments rather than revolutionary action.

Father Jacinto Zamora, born in 1835 in Pandacan, Manila, served as parish priest in Manila and taught at the University of Santo Tomas. Known for his strict religious devotion and conservative theological views, he was not politically active in the reform movement.

His inclusion among the accused appears to have resulted from his association with other Filipino clergy rather than any documented involvement in anti-colonial activities.

The Trial and Execution of the Gomburza Priests

Spanish authorities arrested the three priests in the days following the mutiny. The prosecution alleged that they had masterminded the conspiracy, provided financial support to the mutineers, and coordinated with revolutionary cells in Manila.

The evidence presented consisted primarily of testimony from mutineers extracted under torture and circumstantial associations between the priests and other reformists.

The military tribunal denied the defendants adequate legal representation and refused to allow them to cross-examine witnesses. The proceedings, conducted in Spanish with limited translation, prevented the priests from fully understanding or responding to charges. No physical evidence linked any of the three priests to the mutiny’s planning or execution. Despite these procedural violations and lack of substantive evidence, the tribunal found all three guilty of sedition and treason.

On February 17, 1872, Spanish authorities executed Fathers Mariano Gómez, José Burgos, and Jacinto Zamora by garrote, a method of strangulation using an iron collar at Bagumbayan field (now Luneta Park) in Manila. Thousands of Filipinos witnessed the execution, which Spanish authorities intended as a public demonstration of colonial power and the consequences of challenging Spanish rule.

Father Burgos’s final moments revealed his innocence and resignation. According to witnesses, he maintained his innocence to the end, stating that he forgave his accusers and asking God to forgive those responsible for his death.

The elderly Father Gómez faced execution with quiet dignity. Father Zamora, reportedly in shock, struggled to comprehend his fate until the moment of death.

Public Reaction and Legacy of the Execution

The execution of Gomburza shocked Filipino society and generated widespread outrage. Many Filipinos who had accepted Spanish rule as legitimate began questioning colonial justice and Spanish claims of civilizing mission.

The spectacle of executing three priests on dubious charges without fair trial revealed the colonial regime’s willingness to eliminate any voice of dissent.

Spanish authorities had intended the execution to intimidate Filipinos into submission, but it produced the opposite effect. The martyrdom of the three priests, particularly the respected and articulate Father Burgos, transformed them into symbols of colonial oppression and Filipino victimization.

Their deaths demonstrated that even education, religious devotion, and working within colonial legal structures provided no protection against Spanish repression.

The execution radicalized many Filipino intellectuals and reformists. Those who had previously sought gradual reform through peaceful means recognized that Spanish authorities would not tolerate even moderate challenges to their power.

The event demonstrated that advocating for Filipino equality and rights could result in execution regardless of the legality or peacefulness of such advocacy.

Effects of the Cavite Mutiny of 1872

Immediate Consequences: Spanish Repression Intensifies

The mutiny and Gomburza executions triggered intensified repression throughout the Philippines. Spanish authorities arrested hundreds of suspected reformists, intellectuals, and anyone associated with the secularization movement. Many faced imprisonment without trial, while others received deportation to Spanish penal colonies thousands of miles from the Philippines.

Governor-General Izquierdo banned publications discussing political reforms or criticizing colonial policies. Spanish officials increased surveillance of Filipino intellectuals, monitoring their correspondence and movements.

The colonial government prohibited meetings and associations among Filipinos, effectively ending the nascent public discourse on colonial reforms that had emerged under de la Torre’s governorship.

Spanish friars consolidated their power in the aftermath. They successfully portrayed the secularization movement as seditious and dangerous, justifying their continued control over parishes. Filipino priests lost what limited gains they had achieved, and the transfer of parishes to Filipino secular clergy ceased entirely.

The friars’ political influence over colonial administration increased, as Izquierdo and subsequent governors relied on them to maintain control over Filipino populations.

The repression extended beyond Manila and Cavite. Throughout the archipelago, Spanish authorities suppressed any expressions of Filipino identity or culture that might foster nationalist sentiments. This climate of fear forced reformists to either accept silence or seek opportunities abroad to continue their advocacy.

Long-Term Impact on Filipino Nationalism

The execution of Gomburza profoundly influenced the generation of Filipino intellectuals who would lead the independence movement. José Rizal, born in 1861 and only 11 years old when the executions occurred, later credited Gomburza’s martyrdom as instrumental in awakening his nationalist consciousness. He dedicated his second novel, El Filibusterismo (The Reign of Greed), to the memory of the three martyred priests.

Filipino students who had traveled to Spain for higher education the ilustrados established the Propaganda Movement in the 1880s. This movement sought reforms through peaceful means, including Filipino representation in the Spanish Cortes, equal rights for Filipinos and Spaniards, secularization of education, and freedom of speech and association. The memory of Gomburza served as a rallying point for these reformists, demonstrating both the injustices requiring remedy and the risks facing those who challenged colonial authority.

The reformists established La Solidaridad, a newspaper published in Spain that advocated for Philippine reforms. Contributors including Marcelo H. del Pilar, Graciano López Jaena, and José Rizal used the publication to document colonial abuses and argue for Filipino equality.

While operating in Spain allowed them to escape direct censorship, the memory of Gomburza reminded them of the consequences awaiting reformists who returned to the Philippines.

The Cavite Mutiny and its aftermath revealed the impossibility of achieving meaningful reforms within the colonial system. Spanish authorities’ response demonstrated that they would not voluntarily concede Filipino rights or equality. This realization gradually pushed Filipino intellectuals toward revolutionary rather than reformist solutions.

The Cavite Mutiny as a Precursor to the Philippine Revolution

The path from the Cavite Mutiny to the Philippine Revolution of 1896 illustrates how colonial repression can transform moderate reformists into revolutionaries. The failure of peaceful reform efforts during the 1880s and early 1890s convinced many Filipinos that armed resistance represented the only viable path to change.

Andres Bonifacio, founder of the Katipunan revolutionary society in 1892, represented the next generation of Filipino resistance. Unlike the ilustrado reformists who sought change through publications and petitions, Bonifacio organized a secret society committed to armed revolution. The Katipunan recruited from broader social classes than the elite ilustrados, including workers, farmers, and lower-middle-class Filipinos who suffered most directly from colonial exploitation.

The Gomburza martyrdom served as a foundational narrative for the Katipunan. Revolutionary leaders invoked the three priests as examples of Spanish injustice and the futility of seeking justice through colonial institutions. The memory of their execution helped legitimize armed resistance by demonstrating that peaceful reform advocacy could result in the same fate as armed rebellion.

When the Philippine Revolution erupted in August 1896, revolutionaries carried forward the grievances and aspirations that had motivated both the Cavite mutineers and the Filipino secular clergy. The revolution represented the culmination of resistance that had begun with the mutiny 24 years earlier.

While the 1872 uprising failed militarily and triggered brutal repression, it succeeded in planting seeds of nationalist consciousness that eventually grew into a full-scale independence movement.

Significance of the Cavite Mutiny of 1872 in Philippine History

A Turning Point in Colonial-Era Resistance

The Cavite Mutiny marked the transition from isolated, localized resistance to Spanish rule toward a broader nationalist consciousness among Filipinos. Prior uprisings against Spanish authority had typically been regional, focused on specific grievances, and lacking in ideological foundations beyond opposition to particular colonial policies or officials.

The mutiny itself resembled these earlier rebellions, a local uprising driven by specific economic grievances. However, the Spanish response and particularly the Gomburza executions transformed the event’s significance.

By implicating Filipino intellectuals and clergy in an alleged conspiracy, Spanish authorities inadvertently created a narrative linking armed resistance with reform movements, local grievances with national oppression, and economic exploitation with racial discrimination.

This connection between different forms of resistance and various Filipino grievances fostered a more comprehensive nationalist ideology. Filipinos began viewing their diverse complaints, whether economic exploitation, political exclusion, religious discrimination, or cultural suppression as symptoms of a single problem: Spanish colonial rule itself.

This shift from seeking specific reforms to questioning the legitimacy of colonial rule represented a fundamental change in Filipino political consciousness.

Gomburza’s Enduring Legacy in Filipino Identity

The three martyred priests occupy a central place in Philippine national memory and identity. Philippine schools teach about Gomburza as exemplars of courage against injustice and victims of colonial oppression. Their story illustrates how colonial powers maintained control through violence and intimidation while providing a counter-narrative of Filipino resistance and moral authority.

José Rizal’s dedication of El Filibusterismo to Gomburza elevated the three priests to permanent prominence in Philippine literature and nationalist discourse. Rizal wrote: “To the memory of the priests, Don Mariano Gomez (85 years old), Don Jose Burgos (30 years old), and Don Jacinto Zamora (35 years old).

Executed in the Bagumbayan Field on the 28th day of February, 1872.” This dedication ensured that every Filipino reading this foundational nationalist text would encounter the Gomburza story.

Contemporary Philippines commemorates Gomburza through monuments, street names, and institutions bearing their names. The site of their execution at Luneta Park includes a memorial acknowledging their sacrifice. Their story remains relevant in discussions of justice, human rights, and resistance to oppression in modern Filipino society.

Lessons from the Cavite Mutiny for Modern Filipinos

The Cavite Mutiny and Gomburza executions offer enduring lessons about justice, power, and resistance. The events demonstrate how authorities can manipulate crises to justify eliminating dissent and consolidating control.

The Spanish exploitation of the mutiny to suppress the entire reform movement illustrates tactics that authoritarian regimes continue employing: exaggerating threats, creating conspiracy theories, using show trials to legitimize repression, and making examples of prominent dissenters to intimidate others.

The story also reveals the power of martyrdom in shaping national consciousness. The Spanish executed Gomburza to demonstrate their power and intimidate Filipinos into submission, but the executions instead delegitimized colonial rule and inspired resistance. This outcome illustrates how oppressive actions can undermine the authority they seek to reinforce.

For contemporary Filipinos, the mutiny represents the importance of remembering historical injustices and honoring those who suffered for advocating rights and dignity. The progression from the mutiny through the Propaganda Movement to the Philippine Revolution demonstrates that meaningful change often requires sustained struggle across generations.

The mutineers of 1872 did not live to see independence, nor did Gomburza or even José Rizal, yet their sacrifices contributed to eventual freedom.

Cavite Mutiny Summary: Key Takeaways

Quick Recap of Events, Causes, and Effects

The Cavite Mutiny of January 20, 1872, began when approximately 200 Filipino soldiers and arsenal workers seized Fort San Felipe in response to the abolition of their tax and labor exemptions. Spanish forces quickly suppressed the uprising within 24 hours.

Governor-General Rafael Izquierdo characterized the mutiny as part of a larger conspiracy and used it to justify arresting hundreds of suspected reformists throughout the Philippines.

The most significant consequence was the execution of three Filipino secular priests, Fathers Mariano Gómez, José Burgos, and Jacinto Zamora on February 17, 1872. Spanish authorities implicated these priests in the alleged conspiracy despite lacking substantive evidence.

Their execution shocked Filipino society and radicalized many intellectuals who had previously sought reforms through peaceful means.

The mutiny’s causes included economic grievances from abolished privileges, political repression under Governor-General Izquierdo, and religious discrimination against Filipino secular clergy. Its effects encompassed immediate intensification of Spanish repression and long-term contribution to Filipino nationalist consciousness that culminated in the Philippine Revolution of 1896.

Why the Cavite Mutiny of 1872 Still Matters Today

The Cavite Mutiny remains significant because it represents a pivotal moment when isolated grievances transformed into broader nationalist consciousness. The event and its aftermath demonstrated that Spanish colonial authorities would not concede Filipino rights through peaceful reform, pushing moderate reformists toward revolutionary solutions.

Gomburza’s martyrdom continues resonating in Philippine culture as a symbol of injustice, courage, and sacrifice for national dignity. Their story reminds Filipinos that freedom and rights often require struggle and sacrifice, and that oppression can unite diverse groups toward common cause.

The mutiny illustrates how historical events, even apparent failures like a quickly suppressed uprising, can profoundly influence national trajectories through their symbolic and inspirational legacy rather than immediate practical outcomes.

Understanding the Cavite Mutiny provides essential context for comprehending Philippine nationalism, the independence movement, and contemporary Filipino identity.

The event connects Spanish colonial oppression with Filipino resistance, demonstrating how injustice generates consciousness and determination that transcends immediate defeats to achieve eventual liberation.

Works Cited

Agoncillo, Teodoro A. The Revolt of the Masses: The Story of Bonifacio and the Katipunan. University of the Philippines Press, 1956.

Agoncillo, Teodoro A., and Milagros C. Guerrero. History of the Filipino People. 8th ed., R.P. Garcia Publishing Company, 1984.

Constantino, Renato. The Philippines: A Past Revisited. Tala Publishing Services, 1975.

De la Costa, Horacio. The Trial of Rizal. Ateneo de Manila University Press, 1961.

De Viana, Augusto V. “In the Name of Gomburza: The Cavite Mutiny, Martyrdom, and the Making of a National Symbol.” Philippine Studies: Historical and Ethnographic Viewpoints, vol. 64, no. 1, 2016, pp. 3-28.

Guerrero, Milagros C. “The Cavite Mutiny of 1872.” Kasaysayan: The Story of the Filipino People, vol. 5, Asia Publishing Company Limited, 1998.

Schumacher, John N. The Propaganda Movement, 1880-1895: The Creation of a Filipino Consciousness, the Making of the Revolution. Ateneo de Manila University Press, 1997.

Schumacher, John N. “The Cavite Mutiny: Towards a Definitive History.” Philippine Studies, vol. 59, no. 1, 2011, pp. 55-81.

Tavera, Trinidad Hermenegildo Pardo de. La Revolución Filipina. Imprenta de M. Minuesa de los Ríos, 1898.

Zaide, Gregorio F., and Sonia M. Zaide. Philippine History and Government. 6th ed., All-Nations Publishing Co., 2004.